History of the Governor’s Council

Origins and Colonial Foundations

The Massachusetts Governor’s Council began in 1629 as the “Council of Assistants,” elected by freemen of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This early body combined legislative, judicial, and executive functions, with members ruling on legal cases and shaping colonial law. Among its more controversial figures was Isaac Royall Jr., a wealthy slaveholder whose family money helped found Harvard Law School. His legacy, and its connection to slavery, is now acknowledged at the Royall House and Slave Quarters Museum in Medford.

British Rule and Charter Changes

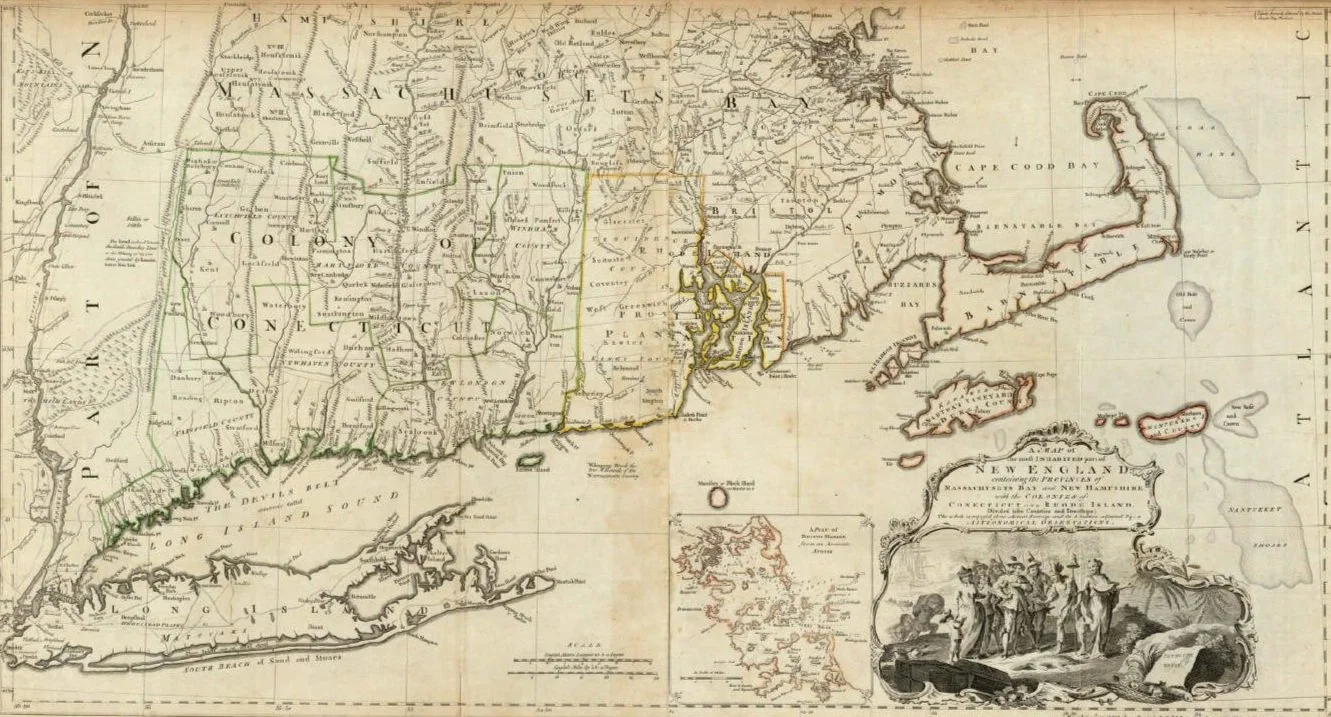

The original colony charter was revoked in 1684, leading to the short-lived Dominion of New England. By 1691, the Province of Massachusetts Bay was formed under a new charter that introduced a more formal “Governor’s Council” of 28 assistants. Appointed annually by the legislature, the Council advised the royal governor, assumed power in their absence, and approved militia commissions. However, its judicial powers were stripped—appeals were now handled by local courts or, in significant cases, by the King’s Privy Council.

"David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries."

The Revolutionary Shift

From the 1760s to the 1770s, the Council's loyalties shifted away from British interests and toward colonial resistance. In the years leading to the American Revolution, Councilors opposed British troop occupation and the Stamp Act. When the royal governor fled, the Council effectively became the executive branch of Massachusetts, helping to steer the colony through wartime governance.

Post-Revolution Reforms

After independence, the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution created the state’s current bicameral legislature. Many of the Council’s former legislative duties were absorbed by the new Senate. Still, the Council retained executive functions and remained a key check on gubernatorial power.

From the colonial era until 1854, Councilors were selected by the state legislature. In 1854, following a push from the Know-Nothing movement, the process changed to direct election by the people. Residency in a district is not required to run, and the Lieutenant Governor serves as chair.

Changes in Succession and Structure

Originally, the Council was in the line of succession should both the Governor and Lieutenant Governor be unable to serve. That changed in 1918 when the state amended its constitution, placing the Secretary of the Commonwealth, Attorney General, Treasurer, and Auditor ahead of the Council in succession.

Today, the Governor’s Council (also called the Executive Council) consists of eight elected members, each representing a district composed of five state Senate districts. Councilors are elected every two years. If a seat becomes vacant, it can be filled by a concurrent vote of the legislature or, if not in session, by the Governor with Council approval.